TOM FRANCIS

REGRETS THIS ALREADY

Hello! I'm Tom. I'm a game designer, writer, and programmer on Gunpoint, Heat Signature, and Tactical Breach Wizards. Here's some more info on all the games I've worked on, here are the videos I make on YouTube, and here are two short stories I wrote for the Machine of Death collections.

Theme

By me. Uses Adaptive Images by Matt Wilcox.

Search

Games Vs Story 2

I was away in London at the weekend, with my laptop but no internet, so I took a break from coding to think about how story might work in my next game.

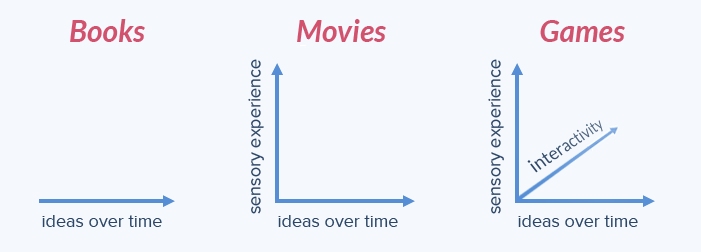

For Gunpoint, I made a video about how fixed stories clash with interactive games, and how I was trying to avoid that:

My solution was to simply separate the two: the story is a pre-written thing that happens between the missions, and the missions are interactive playgrounds in which no plot events occur. The story is a bit interactive too, but only in certain limited ways I could easily account for.

Last week Terence Lee, of Dustforce fame, posted a huge examination of this topic on their blog, and over the weekend I finally finished reading it. It’s worth diving into if you like thinking about this stuff: its conclusions are familiar, but tracing the individual steps there lets you examine the issues in detail. I took about 800 words of notes while reading.

Adding that to my existing thoughts on the problem, here’s a summary of what the issue is, what the solutions might be, and which ones I think I’m going with for my next game.

The problem

- Stories are usually fixed. Usually a story ‘teller’ recounts a story that already exists in their mind, true or not.

- The unique thing about games is that they’re interactive: to some extent, the player decides what happens.

- If we let the player have a say in the story, it’s hard to account for all the things they might want to do.

- If we don’t, their actions feel irrelevant, the constraints we put on them feel artificial, and the game is less interesting to re-play.

The solutions

1. Fixed story: in a game like Half-Life 2, the player has no influence on the story at all. You either do what the characters tell you to and it works out the way the writer wrote it, or you die or stop. I pick Half-Life 2 because it makes this work: I loved the game and cared about the story. It doesn’t feel ideal, though. The story doesn’t add anything to the action or vice versa, it was an extraordinary amount of work to create, and the story gets less interesting each time you replay it.

2. Chooseable story: in a game like Mass Effect, all of the story is pre-written, but you often make big decisions about how it plays out. By the end of the series, there are a huge number of possible eventualities for the characters and races that come about convincingly from your decisions. But you’re still only choosing from a discrete number of eventualities that have all been catered for by the writers, which means a lot of work for them and limited possibilities for you.

3. Generate minimal story: in Spelunky, you’re an adventurer delving into some caves. Everything else is generated by the game’s systems, which are universally consistent and create new experiences every time. The trade-off is that what it generates is rather vague in story terms.

You might do something mechanically interesting to save a damsel, but she’s just ‘a damsel’, a mindless placeholder for a person with no character or uniqueness. It does a great job of making you care about these elements for mechanical reasons, but the stories it generates read more like (good, complex) action scenes than anything with plot or character.

4. Generate rich story: a game like Galactic Civilizations 2 puts you in charge of a civilisation and gives you a lot of choice in how you deal with others: war, peace, trade, non-military rivalry, secret deals to screw over other civs, etc. From what I understand Crusader Kings 2 is even richer, letting you hatch assassination plots against particular members of particular royal families to shift the balance of power the way you want.

These games generate high-level story – ‘plot’ – through their mechanics, and express it through pre-written dialogues that may crop up multiple times. That means they might not be entirely convincing – every few turns, the Drengin in GalCiv2 threaten me with the same line of dialogue about demanding tribute. But there are at least named characters saying specific things, and in GalCiv they have a lot of personality.

These games are probably the closest we’ve got to merging interaction and story in a way where both really add something to each other. But they all tend to be about managing a civilisation, which is just one very particular kind of story.

For my next game

Gunpoint mostly used solution 1. After processing this for a few days, and writing a few thousand words of possible approaches and internal argument about them, I think for GHGC I’m going to aim for a combination of solutions 2 and 3: Mass Effect and Spelunky.

I won’t go into how exactly, until I’ve had a chance to try it and see if it works. But the upshot is, I won’t be doing anything completely radical to merge game and story. Just picking the bits I like from things that already work, and finding exciting ways that they click with the concept of this particular game.

Further thinking

I am still interested in ‘solving’ this problem, or at least coming up with a solution that doesn’t have the same drawbacks as the ones listed. But it really takes a game concept that was built specifically to tackle this. GHGC is a specific idea hatched with a very different goal, and one that fits really well with ways we already know game and story can co-exist.

I do have a game idea that would tackle it directly, though, which I hope to make at some point. It comes from questions like these:

- Why are most of the richest story generators about managing people instead of being one?

- If you never read the official Oblivion strategy guide, would you ever know about the orc who runs drugs from Cheydinhal to the Imperial City?

- What if we had solved how to generate cool stories, but we hadn’t solved how to let the player see them?