TOM FRANCIS

REGRETS THIS ALREADY

Hello! I'm Tom. I'm a game designer, writer, and programmer on Gunpoint, Heat Signature, and Tactical Breach Wizards. Here's some more info on all the games I've worked on, here are the videos I make on YouTube, and here are two short stories I wrote for the Machine of Death collections.

Theme

By me. Uses Adaptive Images by Matt Wilcox.

Search

Dad And The Egg Controller

After dad died, trying to be useful, we looked through his office. ‘Office’ is underselling it – there was so much equipment that it could equally qualify as a workshop or even a lab. It had the special kind of ordely chaos of a place filled with a thousand incredibly specific things, meticulously organised by type, when you don’t know any of the types.

I opened a tiny drawer. Ah yes, this is where he kept things that were brass, cylindrical, and slightly ridged. I closed the drawer, my task complete.

On his desk, though, I saw something I did recognise. Something I knew it would be my responsibility to adopt, decipher, and operate. I don’t know if he ever gave it a name, so I will now: it’s the Egg Controller.

–

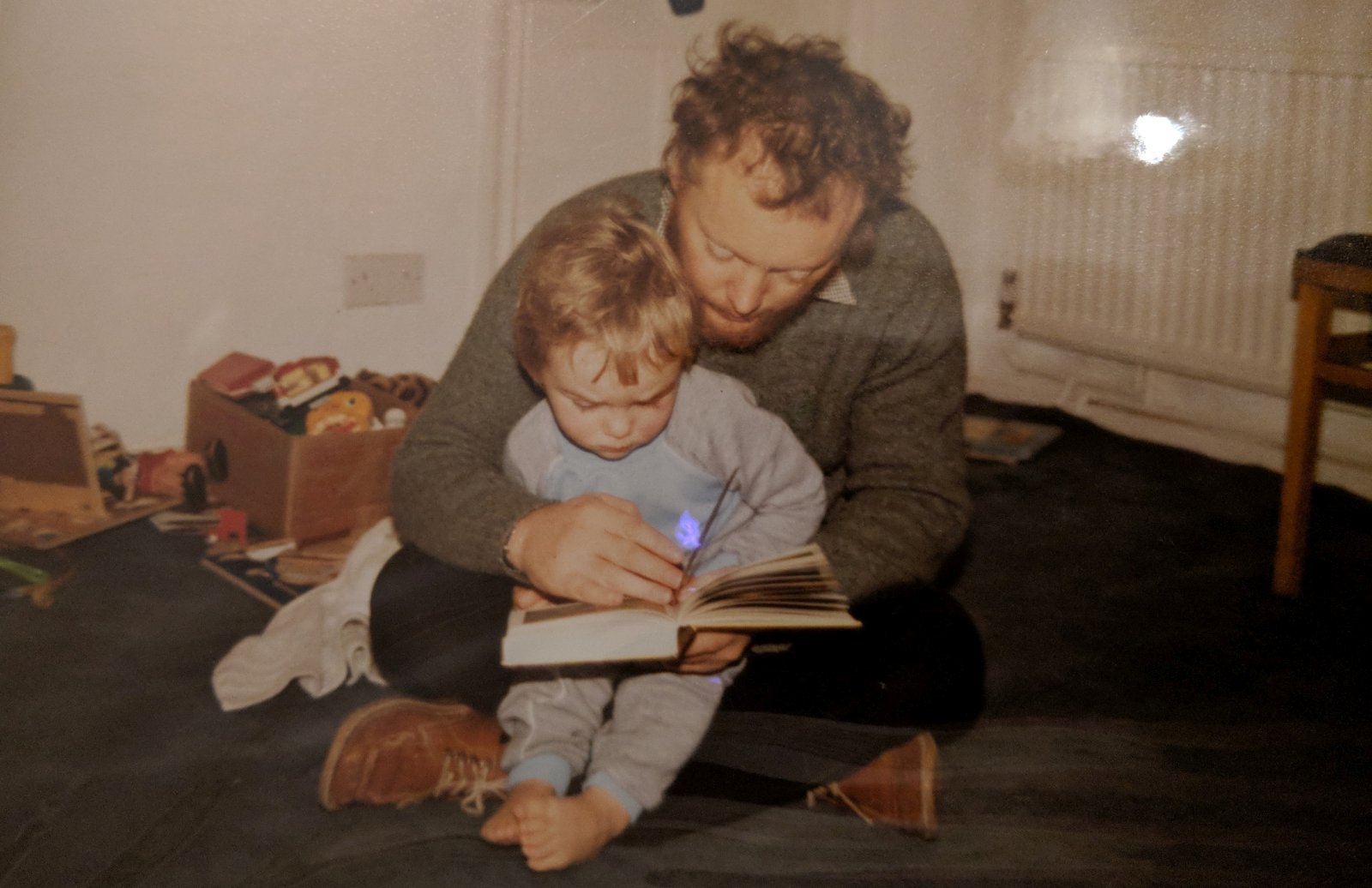

Dad was an inventor. That’s the verdict. When you’re alive, people don’t often summarise you – I suppose it would be rude. I used to tell people he was an electrical engineer, a rather dry job description, but it didn’t sound wrong because I wasn’t trying to summarise him.

Once you die, though, everyone’s required to boil you down to a few words. And I think dad’s come out of that rather well. He was an inventor, and everyone seems to have known it. His creations have been impressing people from the garden shed of his childhood home in Woking, to the mayor of Frome, to a chicken farmer in France, to me, just outside this office, watching him barbecue.

–

To understand the Egg Controller, you must first understand the Egg. The Egg is the Big Green Egg, an enclosed barbecue that’s very good for slow-cooking and smoking things. Dad didn’t invent the Big Green Egg, but he did love to use it. He loved to cook, he loved science, and he loved to be able to provide people with something that was unusually good. Almost anything cooked in the Big Green Egg has a nice smoky flavour to it, and almost anyone who ate something he cooked in the Big Green Egg would remark, “Ooh, it’s got a nice smoky flavour to it!” I think he got a lot of pleasure out of that.

He even cooked our Christmas turkey in the Big Green Egg every year – every year except one. About three years ago, he was ill, and the task fell to me. And this is when I discovered what an enormous pain the arse it is to use.

In theory, it can keep its temperature perfectly stable for hours on end. In practice, you open the vents a bit to get the temperature up, then close them a bit, and it keeps going up. So you close them more, and now it’s going down. So you open them more, and now it’s going up. Leaving it in either state for six hours would result in either cold turkey or festive ash, so you end up having to check on it every fifteen minutes, for six hours.

This bothered me because it was exhausting, it was boring, and it was Christmas. Dad was a lot more devoted to creating good food than me, so I don’t think he minded that. But I think it bothered him for a different reason: it was solvable. This business of making small adjustments, observing their effect, and reacting accordingly was something computers are perfectly capable of. So he set about building one to do it.

–

I’ve inherited this gene, I think. I can’t build gadgets like dad could, so the set of problems I see as solvable is different, but if I feel a solution should exist I will bloody-mindedly create it.

At one point I wanted to get business cards made that would each have a free copy of my game on them. That meant each card needed a different code printed on it. I had 200 codes, and one image with a blank space for the code to be written. The card company would happily take 200 different images, but they couldn’t combine the images and text for me – I had to do that. A solution for this should exist.

It does, actually, there are dozens. But all of them would require me to learn some new scripting language or tool that was far more complex than what I needed. This was a programming problem, and the only programming language I knew was the one I made the game in: it’s called Game Maker.

So, technically, I made a game. It’s a game where the only level is a giant room that looks like my business card, the menu system writes a giant code across it, then it takes a screenshot. Thirty times a second. You win the game by waiting for 7 seconds. Then when you quit, you have a folder full of 200 images, each with a different code on them, which you can send straight to the printers.

This took about three hours to make. How long would it have taken to manually put 200 codes on 200 cards? Look, I’m not on trial here, this is about dad, let’s get back to that.

What dad built, in basic terms, was a tiny computer, programmed with custom software he wrote, hooked up to a thermometer and a fan. The computer gets the temperature from the thermometer, and turns the fan on or off to control the flow of air into the barbecue.

What dad built, in even more basic terms, was two green boxes with buttons and screens on, a black box with a light on it, a metal plate with another black thing in it that could be a fan, two wires that end in crocodile clips, and two wires that end in long metal spikes.

I understood the principles well, but I had a crucial question about the device itself. How do I turn it on?

The crocodile clips are attached to wires which are attached to a briefcase-sized device that I think is called an oscilloscope. I didn’t know much about it, but I was fairly sure you don’t bring an oscilloscope to a barbecue. They must attach to some other power source, but what?

–

As someone with a lot of experience with technology, I usually approach every technical challenge with a healthy acceptance that I may be completely unable to solve it. But the stakes felt higher for this. My last visit before he died, dad had wanted to give me a lesson in this, but we didn’t get to it. Should I have made sure it happened before I left?

He also hadn’t had much time to use this gadget before he died. If I couldn’t figure it out, it would be like all his hard work on this brilliant device was wasted, all because I couldn’t even take that trivial last step of figuring out how to work it. He wouldn’t have been disappointed in me, he never made me feel that was ever a possibility. But I’d be disappointed in myself.

I got excited when I found a likely-looking battery pack nearby, and hooked the clips onto it, but the screens stayed dark. Normal batteries were out – there’s nothing to clip on to. I looked around the room of a thousand unidentified objects, and didn’t like my chances of finding the right one.

Then I remembered – 9 volt batteries do have something to clip onto – those weird little cup things that tingle if you put your tongue on them. Not that I’ve tried that, I’m not on trial here, let’s get back to dad.

I dug one out and hooked it up. The screens… stayed dark.

Then I tried the clips the other way around. Brilliant green letters appeared on the screen. The Egg Controller worked.

I remember a car journey with dad, maybe two years ago, when he was working on the Egg Controller and I was working on my space game, Heat Signature. I was telling him about a programming problem I was having: I was trying to get my spaceships to slow down just in time to stop at a particular point in space, but they kept overshooting or falling short. Something was making the maths trickier than it should have been, so I was telling him how I planned to fix it. I was going to teach my spaceships to pay attention to what affect their brakes were having in practice, and ease off or brake harder based on that.

As it happened, dad had recently solved basically the same problem for the Egg Controller. If you just program it to turn the fan on when the temperature is too low, and off when it’s too high, it will endlessly overcompensate. It takes a while for the effect of its actions to be reflected in the temperature it reads from the thermometer, so it needs an intelligent system to know what kind of change to expect, and when.

He told me this is called a Proportional-Integral-Derivative Controller. It’s how cruise control in your car manages to keep a steady speed when the slope of the road changes. I wanted a spaceship to stop exactly at a space station. He wanted a turkey to stop at exactly 72 degrees celsius. The principle is the same.

–

We didn’t have a funeral for dad, we had a memorial lunch instead. Ten meat eaters were coming, and I was tasked with using the Egg Controller to slow-cook a shoulder of pork for them. It was a fitting use for his brilliant gadget, and for all the same reasons it was fitting, it would be an especially crushing, deeply personal disaster if anything went wrong. On the plus side, I had managed to turn the thing on.

I decided I’d need a practice run. Just a couple of chicken breasts, only one guest. I figured out how to fit the Egg Controller’s fan into the bottom of the barbecue, rigged up both the thermometers, lit the barbecue and examined the screen. It has three columns: Time, Oven and Meat – the three certainties in life. You can set a desired value for each of these, and below it the actual value is reported.

My best guess at how it worked was this: it’ll keep heating up the barbecue until its internal temperature hits what you set under ‘Oven’, then keep it there until the thermometer you put in the meat reaches the tempereature you set under ‘Meat’. And you don’t touch the Time dial because you don’t know what it does.

I set Oven to 180 and Meat to 75. The Egg Controller told me the Big Green Egg was currently only 50 odd, so it had a way to go. Sure enough, the fan it was wired to was blowing away quietly to stoke the fires.

80 degrees.

120.

150.

180. Good!

190. Hmm. The fan’s still going.

195. Fan still going.

200. Fan still going. This doesn’t seem right.

210. OK, this is just never going to stop.

Maybe it just keeps going full blast until the meat gets up to temperature? I tried turning that number down to lower than the meat already was. Fan still going.

Maybe it’s because I didn’t set a time? Was zero time the same as saying ‘never stop’? I tried setting a short time, and waited until it expired. It beeped, but the fan kept going.

240 degrees now, and for the chicken’s sake it was time to intervene. I unhooked the Egg Controller’s fan and finished it off the old fashioned way, endlessly adjusting the vents. We ate the admittedly delicious chicken – it had this nice smoky taste – and I despondently accepted I could not decipher dad’s design.

–

I didn’t want to believe the interface was bad, and I didn’t want to believe I wasn’t clever enough to figure out a good one. I especially didn’t want to believe it was just broken. But there didn’t seem to be any other explanations.

Silly as it sounds, not being able to figure this out made dad feel more distant. I had thought of us as like minds, and it made the loss easier to accept. His brain wasn’t entirely gone, I still have a partial version of it in my own head. But either this gadget did nothing intelligent at all, which couldn’t be true, or he and I thought so differently that even with unlimited tries, I couldn’t deduce how his interface was ever supposed to work. It was an upsetting thought.

“I’d just like to see it ever stop, under any conditions.” I remember griping as I fiddled with the now un-Egged Controller after dinner, still vaguely hoping to find a trick to it. Fan still going.

That was when I saw the red light. I’d been looking at the screens, and the fans, and the thermometers, all of which seemed to be doing their jobs. But there’s one other component – just before the fan, there’s a black box. The black box had a bright red light on it. Aren’t red lights usually bad? I flicked a switch on the box. The light went blue. The fan stopped.

The fan stopped!

I tried turning the desired temperature up again. The fan started!

Near as I can tell, the black box is some kind of controller or regulator that cuts power to the fan when the computer tells it to. When it’s off, instead of cutting power to the fan, it never interrupts it. That’s why I’d never looked for another switch to turn on – if anything, it was too on.

The whole thing worked exactly as I’d first assumed, you just have to flick the mysterious switch on the black box first. Dad and I do think alike. Except on the subject of black boxes and what should happen when they’re off.

On the morning of the memorial lunch, I was up in good time and had the barbecue lit, the Egg Controller hooked up, and the pork on by 9am. I had Oven set to 110, Meat set to 87, and I didn’t touch Time because I didn’t want to jinx things, but I was allowing four hours til lunch.

50 degrees.

80.

100. Fan still going.

110. Fan still going. Come on…

111. Fan stopped!

110.

109. Fan starts!

110.

110.

110.

The spaceship has stopped at the station. The car is successfully cruising. The Egg has been Controlled.

It worked perfectly. The little fan would spin up and wind down every now and then, and the temperature was dead on nearly 100% of the time, only dipping or rising 1 degree for a moment now and then. Dad would have been proud. He might have even said it was “Quite neat, actually” – his strongest possible praise for a gadget.

I had half-hoped to do pulled pork, time permitting, but I’m new to the world of slow-cooking and it turns out 4 hours is rushing it. I had to cook it a little faster to make sure it was ready in time, but with the Egg Controller that was a simple turn of a dial, and the computer handled the rest.

The Egg Controller draws a graph of the meat’s internal temperature over time – of course it does, dad made it – and this rose from a gentle slope to the side of a mountain. The meat reached 87 degrees right before 1pm, the Egg Controller gave a satisfied beep, and I hauled the impressive-looking joint out to carve it up.

It needed slicing rather than pulling, but it was devoured in short order, and more than one person said “Ooh it has a nice smoky flavour!”

I think dad would have got a lot of pleasure out of that.