TOM FRANCIS

REGRETS THIS ALREADY

Hello! I'm Tom. I'm a game designer, writer, and programmer on Gunpoint, Heat Signature, and Tactical Breach Wizards. Here's some more info on all the games I've worked on, here are the videos I make on YouTube, and here are two short stories I wrote for the Machine of Death collections.

Theme

By me. Uses Adaptive Images by Matt Wilcox.

Search

Blood Money And Sex

Update 2016-03-01: Since this post still comes up occasionally, I’ve edited it to be a bit less dickish.

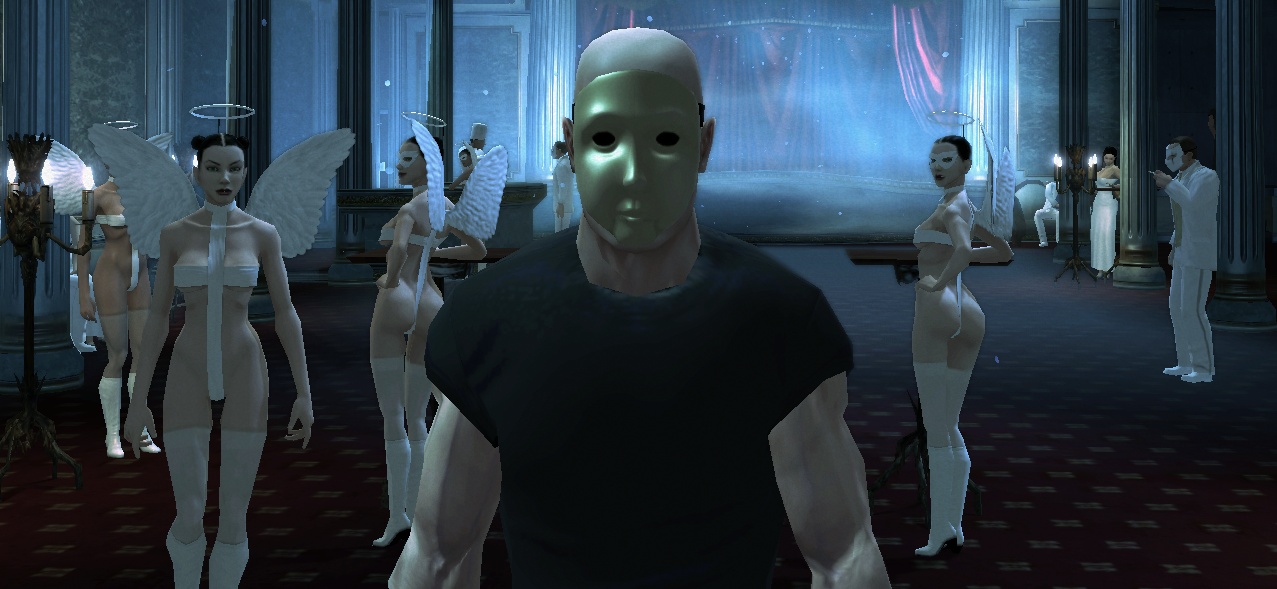

The women in Hitman: Blood Money are grotesquely over-sexualised, which is not unusual for a videogame, but I think the reason for it might be. Blood Money’s vision of the world is stylised to let us see it through the eyes of the hitman: a sociopathic clone completely disconnected from human nature. To make someone see the world the way your character does, make the world the way the character sees it.

Its characters are oversexualised in a profoundly unsexy way – both genders are luridly exaggerated beyond attractiveness. The Hitman is asexual, and people’s sexual attributes and inclinations appear exaggerated and repulsive to him. Hence the chesty women, the muscle-bound men, and the endless sex-talk (conversation topics range from “fucking”, “who I’d like to fuck”, “I’m drunk and would like to fuck you”, “how hot are these girls?”, “wow these girls are hot”, “let’s fuck later”, “I’m going to fuck you later”, “I want to fuck you”, “would you like to fuck?”, and “here’s some aphrodisiac to help with the fucking”) . It’s shoved in our face to make us as disgusted by it as a cold, sexless killer would be. I think it even wants you to hate them a little bit, to let you see how someone like this can kill without hesitation or remorse.

The Hitman is usually thought of as something of a blank-slate protagonist, but he’s actually one of the best examples of effectively putting the player in his avatar’s shoes. You’re made to feel something of the way this anti-hero feels just by the filter through which he sees the world, but what he does in response to it is still up to you. The genius of it is that they’re portraying a character by how they paint everything but the character, rather than dictating the character’s actions or story.

One of the reasons games are so exciting as a young artform is that developers are just discovering tricks like this. It’s not entirely new to Hitman: it’s had huge breasts and permanent scowls since the first game. The second one made you feel 47’s disconnection from other people by sending you almost exclusively to foreign-language countries, and the third externalised his stormy disposition by setting every flashback mission on a dark and rainy night – even ones which actually happened by day. But Blood Money’s sex angle is the most efficient ploy so far, and like every aspect of the fourth game, feels like the idea finally coming of age.

The rest of this post is just about the mechanics of Hitman and what I like about them and how they could be improved, which probably should have been a separate post but it’s too late now.

Social Situations And Silenced Weapons

Hitman has always been extraordinary for mixing violence in with polite society, but control, interface and AI quirks have often interfered with the fun. Those are almost entirely gone now, and Blood Money is genuinely the game the series always wanted to be. It’s the first time they’ve consistently kept all the important elements together:

Fuzzy suspicion: Actually this one is largely new, and finally doing it right is the main reason Blood Money is so much better than previous Hitman games. Guards are just a bit more human in how they react to suspicious behaviour, in that they no longer open fire the second you step out of line. That single tweak removes 90% of the frustrating moments a Hitman game normally inflicts on you. It also adds another freedom: the ability to get past AI guards with misdirection and trickery, rather than stealth or violence. My current favourite approach is to just slightly irritate people:

a) My target and his girlfriend are making out in a corridor. I turn the light off. He irritably barges past me to turn it back on, and they retreat to his room for some privacy, but the moment is gone and the girl walks out for some air. As she leaves, I slip in and throttle him. I am the mood killer. Also the killer.

b) A handyman is repainting a doorway to the maintenance tunnels I need to get to. I can’t kill him because the cop opposite takes only very brief breaks from his watch. Instead, I nab his toolbox and toss it across the room with a clang. Annoyed, he goes over to fetch it, and while he’s occupied I stroll through the door.

c) Two guards man the monitors in a security booth overlooked by a CCTV camera. They’re close enough that neither can be killed without alerting the other, no matter where their attention is turned. I back round the corner, and throw my gun into their line of sight. It’s a dangerous item, so of course one of them has to confiscate it and take it to the security HQ in the main building. While he’s away, I throttle his partner, steal the camera’s tape, and take his clothes so that the main building’s reception guard won’t think anything of it when I follow the gun-confiscator into the security HQ – a nice quiet place to strangle him and take my gun back. Psych!

Public areas: without these it’s just a stealth game, a simplistic and degenerate genre compared to Hitman’s actual multi-faceted magnificence. Masses of Hitman missions have lacked a space for you to move around in without disguise or subterfuge, a calm initial phase to the hit in which you can observe patterns and plan your approach. Wonderfully every single one of Blood Money’s jobs includes one, and it ensures you the quintessential Hitman experience – walking around unnoticed, observing routines, seeing a social situation in a killer’s terms: who can be taken out quietly, where the body will go, how attention can be diverted from that door. These considerations exist in hostile environments too, but it’s a stressful and constrictive situation. It’s only fun when you’re allowed to be there, but not to do what it is you must do. It adds an element of audacity: when everyone’s out to get you, killing is just a survival tactic. In Hitman, everyone’s happily going about their lives in normal society, and you’re going to stride in and do something massive and terrible and get away with it.

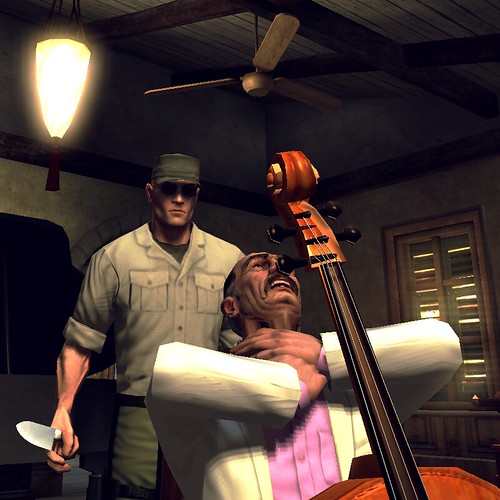

Subtle kills: Subltety and elegance barely featured in the original game, but as Hitman matures it starts to appreciate the finer things in murder. A simple squirt of a syringe, the turn of a dial on a pyrotechnics control panel, the clicking of a detonator, the unseen flinging of a kitchen knife, a short sharp shove to a precariously positioned target, or the removal of a prop gun and the placing of its working counterpart. Approaches that take masses of planning, but which manifest themselves in a single, simple, silent easy action. Blood Money invented most of these options, and by cramming every mission full of them, moved from the pre-scripted puzzle-solution feel of Contracts to a playground of homicidal oppourtunity.

A wealth of interesting options: In general, too, there’s a gorgeously rich possibility space. Full not just of ways to succeed, but cool, dramatic and stylish ones. They made twelve of the best Hitman missions ever, then just kept on making them, again and again, in the same environment with the same targets, adding superfluous alternatives just to suit the depraved stylistic preferences of their players, or simply to increase their chances of stumbling upon something brilliant. Steve and I have spent more time talking about alternative approaches to Blood Money’s missions than I have playing Contracts’.

Meditations On Murder

I’d like to fix Blood Money. It makes one giant mistake, and introduces three new systems that don’t quite work.

Saves: WHAT. The first two limitations are simply mad – you can save seven times, but only in three slots – and only on Tuesdays? Do we get an extra save if we own a domesticated meercat? How about only letting us save when we’re facing Mecca? But the third is criminally derranged. The game will delete – it will fucking delete – your save games if you need to quit or restart. It will delete them. It DELETES them!

Upgradable Weapons: A nice idea, using the money from jobs – and bonuses for style – to bolt on silencers, scopes and new ammo types to your favourite bit of kit. For some reason, though, they decided to make these so cheap that even an inept hitman can afford to buy virtually all of them at every stage. To counter-act that self-inflicted spanner in the works, they then locked off the good upgrades until you reach a certain mission. Despite being the rationale behind the very title of the game, money becomes irrelevant and only progress restricts your weaponry – for no coherent in-game reason. It’s not a huge problem, but it would be so easy to make it so good: just make everything expensive. Let me spend all my earnings on a really good silencer after the first few missions, if that’s how I want to play. I’ll still look forward to getting accuracy and damage upgrades later on, and I won’t be able to afford the good ones until the very end.

Notoriety: The more witnesses you leave, the better photofit the police have of your face, the more likely guards are to get suspicious when you act out. “Hey, isn’t that guy clambering over the compound wall the one from the paper the other day?” But for some reason it’s not based on the number of witnesses – bodies found while you’re still at the scene or just lots of unnecessary killing also increase your notoriety.

It’s obvious two separate metres are needed: Recognisability and Heat. Recognisability is entirely down to witnesses escaping alive and security cameras catching you, and represents how good an idea the police have of what you look like. Heat is down to how many people you’ve killed, and represents how high a priority you are for the police. If you’ve killed hundreds of innocent people but no-one’s ever lived to tell the tale, they’ll want to find you badly but guards will be no more suspicious of you than anyone else. Security will be increased, but you’ll be able to get away with the same things. If you’ve only ever killed your targets and no-one else, sticking to non-lethal takedowns for anyone else in your way, security will be lighter throughout. But if people or cameras have seen you and got away, those few guards will be harder to slip by. Apart from making more logical sense, the point of separating out Heat is to compliment the player’s style. If he likes killing loads of people, increased security will be fun but challenging for him, and he’s not punished. If he doesn’t, but did it because a plan went wrong, the increased security ups the stakes and encourages him to get the subtler methods right.

Accidents: It’s the obvious next step in the subtlety stakes to avoid even the suspicion of foul play, but in Blood Money it’s not quite well-developed enough to be a viable goal throughout. Nearly all of the targets can be killed with accidents, but a) a few can’t, and b) there’s no reward for pulling it off. I’ve heard that the plan was for the post-mission newspaper article to be just an obituary if the death looked like an accident, which would have been great, but didn’t seem to make it to the final game.

I don’t think accidents are enough. Some of them are extremely suspicious, and there are more inventive ways of entirely avoiding heat: faking suicide, eliminating the body altogether, or framing someone. There’s one opportunity to frame someone in Blood Money – getting the other actor to shoot your target on the opera mission – but there could be more. Stealing someone’s gun, shooting the target, then dropping the weapon at the scene and leaving before anyone else sees you ought to work as a successful frame up. As should knocking someone out, dressing up as them, doing the hit, then switching clothes back. “Honestly, a guy in a suit came and did it! But you won’t find his fingerprints on the gun because he was wearing gloves. Also you can’t see the guy.” Getting rid of the body could be in furnaces, downriver, posted elsewhere (!) or even stolen discreetly from the scene (would require a vehicle, I guess). Suicides could be a simple case of fibre-wiring someone, dragging the body to underneath a light fitting and stringing them up. It doesn’t have to be ultra-convincing, the police in Hitman are intentionally dumb.

The Silent Assassin accolade has a few inconsistencies – bodies found while you’re at the scene mean no Silent Assassin rating, even though all bodies will eventually be found either way, and the speedruns show that it’s possible to get Silent Assassin even when you flee the scene in a hail of gunfire, even in Professional difficulty. The point of this system would be to introduce a new accolade to replace Silent Assassin: Case Closed. It would mean that you attracted 0 heat on the mission, that the police aren’t looking for you at all – a much more satisfying result than having been seen at the scene, and leaving evidence of foul play.

More Game Design Ideas