TOM FRANCIS

REGRETS THIS ALREADY

Hello! I'm Tom. I'm a game designer, writer, and programmer on Gunpoint, Heat Signature, and Tactical Breach Wizards. Here's some more info on all the games I've worked on, here are the videos I make on YouTube, and here are two short stories I wrote for the Machine of Death collections.

Theme

By me. Uses Adaptive Images by Matt Wilcox.

Search

How To Stop Writing A Fucking Book

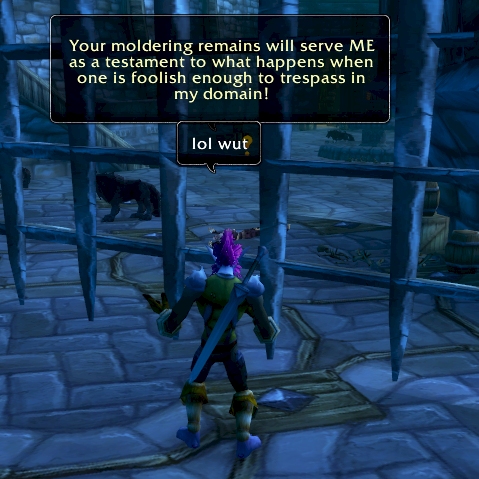

Brief out-of-context quote from Blizzard honcho Jeff Kaplan that made Stardock’s Trent Polack – and me – smile:

“We need to deliver our story in a way that is uniquely video game.”

Every time someone says something like that, I picture a scripted scene playing out some dramatic event that would otherwise have been communicated in text. But of course, that’s not games. That’s films and plays, which Kaplan rightly cites as other things to avoid imitating – games suck at it. Half-Life 2 is remarkable for coming closest, and I remember getting very carried away about its animation at the time, but the truth is Alyx’s ridiculous canned gesticulations would be scoffable in any film.

Mechanics are the main thing “uniquely video game”: this is the only medium where we can learn about something by experimenting with it, toying with it, seeing how it responds to different inputs. But can you tell a story with that? Art game loons like Rohrer certainly seem to suggest story-like themes with their game mechanics. But those same games set out not to tell any particular story, and the zero-writing approach means they’d struggle to anyway.

The cool thing about games is that books can’t show you exactly how a scene looks, and films can’t ask you to read a huge chunk of background text, and music can’t respond to you. We’re absolutely a mish-mash medium, and perhaps “uniquely video game” doesn’t have to mean pulling one magical trick that nothing else can do. Perhaps it means leveraging all the other mediums games comprise, rather than leaning heavily on any one: whether that’s books in World of Warcraft or movies in Gears of War.

The one game that springs to mind as an exemplary case of telling a story in a way no other medium could is my old favourite Masq. It has text and pictures, but not much of either one: it’s simple-looking, simply written and short. But it offers two uniquely video game experiences.

The first time through, it’s a story that responds to you. It’s only multiple choice, but the choices are extremely multiple, and you genuinely do drive the story to an extent I’ve seen nowhere else. (Though I’m sure plenty of text adventures and simple graphic adventures like this compare favourably).

The second occurs after you’ve played it a few times, and you’re really just experimenting. You get to know the characters in a way linear fiction can’t allow: you get to ask, “What would they have done if…” Dozens and dozens of times. It wouldn’t be remarkable, except that there are fascinating quirks to some of Masq’s characters that only become clear when you know them from multiple playthroughs.

Masq can do this because its content – pictures and dialogue for the various eventualities and decisions – is cheap to make. A decision with four possible outcomes doesn’t take impractically long to flesh out. If Blizzard want to tell their story in a uniquely video game way, they have to swallow a bitter pill: the notion that any given player isn’t likely to see most of what they spend their time on. But after filling a world the size of Azeroth with quests, that’s a pill they’ve swallowed in handfuls.