TOM FRANCIS

REGRETS THIS ALREADY

Hello! I'm Tom. I'm a game designer, writer, and programmer on Gunpoint, Heat Signature, and Tactical Breach Wizards. Here's some more info on all the games I've worked on, here are the videos I make on YouTube, and here are two short stories I wrote for the Machine of Death collections.

Theme

By me. Uses Adaptive Images by Matt Wilcox.

Search

He Looks Truly Mortified

Sorry Peanut, I know you were in the middle of your own taunty thing. But I had to try the Heavy’s kill-o-taunt.

I’ve also been punching people’s blood out a lot more lately, and can now see the point of the KGB. If you’re not familiar with Team Fortress 2 and its unlockables, that sentence may have sounded strange.

Having the Sandvich cleverly lures you into the business of punching, because your fists are now your only backup weapon. That in turn makes you realise it’s more viable than you’d expect, and suddenly the idea of getting a bonus for doing it is rather tempting. Five seconds is a long time in 100% critsville – switching to Natascha and spinning up probably only takes one and a halfish.

Halloween 2010

Roughly from left to right: Craig as Dexter Morgan, Kim as The Scout, me as The Spy as Graham Smith, Jim as a witch, Anna as a witch, Graham as Minecraft Guy, Lisa as a dinosaur, Tim as a Murloc, Laura as Red Riding Hood, and Amanda as Sully.

Roughly from left to right: Craig as Dexter Morgan, Kim as The Scout, me as The Spy as Graham Smith, Jim as a witch, Anna as a witch, Graham as Minecraft Guy, Lisa as a dinosaur, Tim as a Murloc, Laura as Red Riding Hood, and Amanda as Sully.

John made these amazing pumpkin desserts in little ramekin dishes, so he’s forgiven for coming as John Walker.

John made these amazing pumpkin desserts in little ramekin dishes, so he’s forgiven for coming as John Walker.

The wrap-around made this even scarier than I’d intended.

The wrap-around made this even scarier than I’d intended.

I eventually discovered for myself how disturbing it is to see someone else wearing your face.

I eventually discovered for myself how disturbing it is to see someone else wearing your face.

Kim’s custom-made dog tags – “BONK!” and “I broke your stupid crap moron!”

Kim’s custom-made dog tags – “BONK!” and “I broke your stupid crap moron!”

I did not spend a lot of the evening with my mask correctly aligned.

I did not spend a lot of the evening with my mask correctly aligned.

And making this video is why Rich Cobbett is forgiven for coming as Rich Cobbett.

In reference to this.

Pumpkin carving the previous night.

Pumpkin carving the previous night.

This was mine, a dramatic departure from last year’s.

This was mine, a dramatic departure from last year’s.

Half-Life 3: Episode 1

We didn’t make hats this time, but I booked the office as late as it goes (22.00), we got some Chinese food in and hung around for the release time, Craig, Graham and I. The worldwide simultaneous online launch is one of my favourite things about the Half-Life experience now, I absolutely love the feeling of a global unwrapping of this insanely exciting present. My office PC hadn’t preloaded it, absurdly, impossibly, maddeningly, so I had to scramble round to Tim’s and try not to look at Craig’s screen as he was first in. I repeatedly shouted “Shut up!” at every gasp and expletive it inspired, and tried to ignore Graham’s reaction as he got to the same bits. After scrambling wildly to install my mouse on Tim’s machine (I wasn’t about to settle for a freaking Microsoft one for something as important as this), I finally got in about fifteen minutes late, and played until Security kicked us out, which was oh-so-perfectly just as I reached the end.

Oh yes, the title – it does say Half-Life 2: Episode One on the title screen, but Gabe Newell consistently refers to this as Half-Life 3: Episode One, and indeed this episodic trilogy as the entirety of Half-Life 3. And I think its important to acknowledge the momentousness of the event – this isn’t a stopgap, this is it.

That beginning: holy shit. I don’t understand the technical bits of how the Source engine has changed, but that sequence so massively exceeds your expectations of how good Half-Life 2 can look that it suddenly feels like something properly new, not just Half-Life 2 deleted scenes. Valve have always been the only people who can make game characters touch each other properly, and the interaction between the Vortigaunts and Alyx at the start is one of the most extraordinary bits of animation I’ve ever seen in a game. All the other most extraordinary bits of animation I’ve ever seen in a game happen in the next five minutes, and most of them are on Dog.

One, of course, is being hugged. I am being hugged, by a game character. This is… nice. Perhaps slightly nicer than it has any right to be, given what it actually is. It’s not the last time the force of Alyx’s emotion surprises you – she is utterly flabergasted by your performance at one point, and is genuinely traumatised at another. All three times it jars you out of the mindset in which she is a friendly combatant, rather than a character. The rest of the advances in AI companionship are fixes rather than features – it took Herculean effort to prevent her from being annoying or a liability, but the result is by definition something you don’t notice.

Episode One’s two potential shortcomings cancel each other out: one, it’s short. Two, it’s still in City 17. Three and a half hours every six months works out to a little over one minute of game per day. I actually found its length satisfying – I did masses in that time, so it felt substantial. But it was helped a lot by the fact that I have spent a lot of freaking time in City 17. It’s the defining feature of the Half-Life games that every section is just slightly longer than the human mind can comfortably endure – you’re always a little exhausted after any given section, and it’s designed that way because that’s the threshold past which your brain registers an experience as signifcant. So every Half-Life player remembers Surface Tension intimately, whereas I couldn’t name you or describe a single level of Quake. As ever, it’s just right because it’s just wrong – it’s slightly longer than it was possible for me to enjoy a single setting, so exhaustion set in shortly before it ended, leaving me relieved to be leaving without having suffered for more than a minute or two. More than any other Half-Life location, leaving City 17 is profoundly cathartic. We’ve done, seen and felt so much there that – however wonderful it was – we never want to go back.

Half-Life 2: Deathmatch

The Basics

Guns vs Filing Cabinets. Morons think this is the sequel to Half-Life Deathmatch and run mindlessly around spraying people with the feeble SMG. This is not that game. It’s a game where you fight two classes of enemies – cannon fodder grunts, armed with the standard Half-Life 2 weapons, and Gravity Jedis, artful duellists each with their own remarkable style which will clash with your own in a gripping battle of the titans. You, of course, are a Gravity Jedi. Aren’t you?

The Appeal

The raw physicality of it all. Shooting people with guns is a very hypothetical thing – unless it’s Soldier Of Fortune 2, you’re just clicking to make a hitscan check in code deduct HP from a hitbox until it turns into a ragdoll and gains some decals. If you fire a radiator at someone, you’ve fucking killed them. It’s immediately apparent.

I was enthralled by this. I’ve been playing it from the hour it came out, and while most Half-Life 2 owners toyed with it then rejected it as ‘merely fun’, I haven’t been able to stop. As part of the delightfully evocative shared lingo of some of the PC Gamer writers, we often talk of ‘crushing’ our enemies – this is the game where you can actually do it. Crush. No armour check is made, no super-health can save them, they can scour the whole map for the best weapon in the game – they’ll find, when you Gravity Gun an eight foot metal workbench into their neck, that they had it all along.

That ‘great equaliser’ element adds a beautiful twist to it. I am good at HL2DM, and when I’m at the top of the scoreboard, the idea that I got there with the starting weapon, the one everyone has all the time but doesn’t use, is uniquely satisfying. Only the élite stick to the Gravity Gun, and when you meet a fellow one the battle is extraordinary. Objects ricochet off each other in mid-air, rebound off walls and are re-caught before they hit the ground. Every piece of furniture, debris, wall-fitting and data storage device is vacuumed up and flung in relentless yet fluid exchange. Lesser players are smashed in the crossfire, casual shots catching them in the face, tables hitting the ceiling and dropping on them. It almost looks like an unhappy coincidence that everyone using a gun dies within seconds of entering the room, but there is something subtle but unmistakable in the way a Gravity Jedi moves, his instinctive feel for physics and his inhuman catching reflexes that renders him impervious to the hail of metal and plastic that pounds the rest of the room. When the first blow finally hits, it is the last – one is too busy catching the last throw of the other, or scooping up his next projectile, and a sink crashes into his skull. The victor stands up in his seat, punching the air. The defeated player shakes his head in deference, awe. Someone is as awesome as he.

The Essential Experience

The radiator kill. I could list my top fifty Gravity Gun objects without pausing, but top of the list is always the ridged wonder. Slim one way, broad the other, deadly both. Brutal mass, perfect ricochet, flat-surface slide factor high. Warm glow.

Half-Life 2 Speedrun Is Beautiful, Ugly

The part where players invent unpowered human flight, and the part where they use the HEV suit’s optical zoom to look at a butt, are the two defining acts of the hardcore gaming zeitgeist.

YouTube commenter nobody960814 explains the trick:

“To prevent bunny hopping, valve created a system where repeated jumping should slow you down. Unfortunately they implemented it by applying a force on you in a direction opposite to the way you’re facing, not the way you’re going. So by bunny hopping backwards, you can accumulate ridiculous momentum.”

Half-Life 2

The Basics

Sci-fi FPS in which your character never speaks, we never leave his viewpoint, and no-one ever bothers to explain the plot to him. He wakes up in an Orwellian future, humanity oppressed by a collective of co-opted and modified alien species. He must help the pockets of resistance he finds to overthrow the jerks. Combat is half shooting and half physics-based, using a device that can drag objects to you and then fire them out at speed.

The Appeal

The gasmask moment, the crowbar moment, the Manhacks moment, the chopper fight, the dam jump, the Gravity Gun moment, playing with Dog, the sawblade moment, the fast zombie moment, the black zombie moment, the Gregory moment, the jeep jump over a gunship, the guided rocket fights, the shotgun-battle stop-offs, the Antlion assault on Nova Prospekt at dawn, Dog versus the APC, the Strider fights, inside the Citadel, the Super Gravity Gun moment, The Explosion. I had higher expectations than anyone, and each of these astonished me. I have never been so impressed by anything in my life than by Half-Life 2. In another game, though, these would be reduced to good ideas, nice touches, memorable experiences. Here, they were mind-blowing. It wasn’t about the actual events, in the end, it was about how convinced I was that they were really happening to me.

They were so detemined that it should feel right, they recreated science itself for their world. For me the only reason to hold ‘linear’ against a game is if it controls where you’ll be and what you’ll be doing in order to avoid the hard work of genuinely crafting a world. No danger of that here – this is the most physically convincing, tangible world short of the real one. Everything you do sounds and feels right, and thanks to the ability to pick things up and throw them (with your hands or the Gravity Gun), you can do an awful lot.

This ‘feel’ I won’t shut up about is only half physics – most of the rest is the absolutely perfect sound. I go around throwing grenades at things just for the sound they make when they bounce off different surfaces. The fact that it is always, always the exact right sound for a small, heavy metal canister bouncing off whichever of the hundreds of surface types I’ve chosen to toss it against, is mind-boggling to me. This is a grenade. Its purpose is to explode. Who the hell cares what the bounce sounds like? It’s going to be muffled by gunfire anyway.

Valve are the only company in the world who know just how much it matters, and have the resources and time to get it exactly right every time. It is perfection, and games have never come close before. The result for the casual player is just better immersion, which is important and everything, but the result for people like me is more profound. We play games out of a sense of adventure, to travel to places more amazing than any on this Earth. But we never expected it to feel as much like a real place as Half-Life 2 does. That’s why I keep going back.

The Essential Experience

Barney throws you your crowbar – great moment. I think for a second, then reload the autosave and do it again. This time, I step back and let the crowbar hit the ground. It clangs against the concrete and clatters to a standstill. The sound, the bounce, the feel is perfect, and yet there is absolutely no reason to account for the possibility that some idiot might jump out of the way of the crowbar just to see what sound it makes when it hits the ground. And they didn’t have to. They just went to the Herculean effort of making a world in the first place, and now every eventuality works perfectly. It can seem a subtle and merely philosophical difference, but if a crowbar falls in the concrete jungle and no-one hears it, it makes a sound. It goes CLANG.

Gunpoint: What I’m Working On

To keep you up to speed, here’s a breakdown of what I’m working on at the moment:

1. Fix the last few Gunpoint compatibility problems

I fixed a lot of bugs pretty quickly in the first four patches, but the last ones left are tougher. Most of them aren’t mistakes in my scripting, they’re fundamental incompatibilities between the engine I used and certain PC configurations. So fixing them means porting Gunpoint to a new engine, and exactly how we do that is a big, complex, important decision for the future of the game. Continued

Gunpoint: Tripping Up

Okay, so neither of us have quite mastered the door technology yet.

Okay, so neither of us have quite mastered the door technology yet.I’ve gone back to working on the infiltration-themed platformer I’m making, Gunpoint. I’d planned to take two days out of the winter break to binge on it, but after a few interruptions I’ve decided four half-days might be more doable, and less exhausting.

The plan is to rapidly impliment the last few features it needs before the main mechanic can make sense, without slowing down to fine tune their operation or tweak the look. So far I’ve got security doors and light switches working, and I’ve almost got the AI interacting with them correctly: only guards can pass through security doors, and they’ll turn on lights if they find them off. Next it’s the main mechanic, then a few last fundamentals that may end up being important.

It’s fun to be making fast progress again. It was a huge mistake to bother putting elevators in before the rest of the basics were working, and the ridiculous time that took added to the ridiculous time AI took is the main reason I ground to a halt on the whole thing.

I now have a game that is ugly, broken and crude in every way except the lifts, which are the most magnificently smooth, reliable and satisfying vertical transportation in the history of interactive entertainment. And I’m about one month behind where I would have been if I’d stuck to stairs. It started to feel hard.

It isn’t, really, but a few things do trip me up repeatedly. I want to make a note of them here on the offchance it gets any of it through my skull, so the rest of this post will make no sense to anyone who doesn’t use Game Maker (the tool I’m making the game with).

Things I Wish I Wouldn’t Constantly Forget

- When you store an instance in a variable – remembering which wall I’ve just collided with, for example – don’t. Store its .id property. Sometimes, even though what you want to reference is a property of that thing, you have to pretend it’s a property of that thing’s id, even though that makes no sense. Otherwise, you get shit like light switches that toggle their own existence on and off instead of changing the light level.

- The Create event is a handy place to put any code that should be executed when the object is created. DON’T EVER FUCKING USE IT FOR THAT. Why? Because the objects in the game at start up are created in an arbitrary, unreadable, undeterminable and randomly changing order.

You have no idea what code has already been done and what hasn’t when any given Create event is executed. So when one tiny change to something suddenly breaks everything in your entire game, including a bunch of stuff it had absolutely nothing to do with, it’s because the Creation order has changed arbitrarily.

Only ever use Create to set initial variables, then use Alarm events to trigger actual code. That way you can set those alarms to go off in the order you specify.

- Often you want one object to ‘trigger’ an event for another object. The reason the method you just tried isn’t working is that it’s getting re-triggered repeatedly sixty times a second all the time that the conditions are fulfilled, usually reversing the effect and/or delaying alarm events indefinitely.

The best way I’ve found to do triggers like this is to have it set an Activate property on the target object. The target object checks this Activate property every step, and the moment it’s ‘true’, it sets it to false, does its work, then tells the trigger object not to bother it again until it needs to.

- Relatedly, attach code to the object it affects, rather than the object that executes it. A button shouldn’t open a door, even if that’s the only thing it’s ever going to do. It should just say “Open!” to the door, and the door itself should contain the code for how to do that. That way, if you ever need other objects to open the door, they can just say “Open!” too and it won’t cause any conflicts or require any repeated code.

Pretty goddamn fascinating, I think you’ll agree. The truth is that most of the problems you encounter creating a game aren’t as frustrating as playing the average shooter. You don’t expect to succeed. You’re wrestling a ridiculous tangle of logical statements into something that functions as a comprehensible world, which is an insane and extraordinary thing to do – even when the results are drab, glitchy and artless. In other words, I’m enjoying it again.

By the end of this sprint I plan to at least be able to show you a video of it in action, and possibly send out a new prototype version to testers. If you’d like to try it when the next version’s ready for testing, and haven’t already mailed me about it, mention Gunpoint in a mail to pentadact@gmail.com.

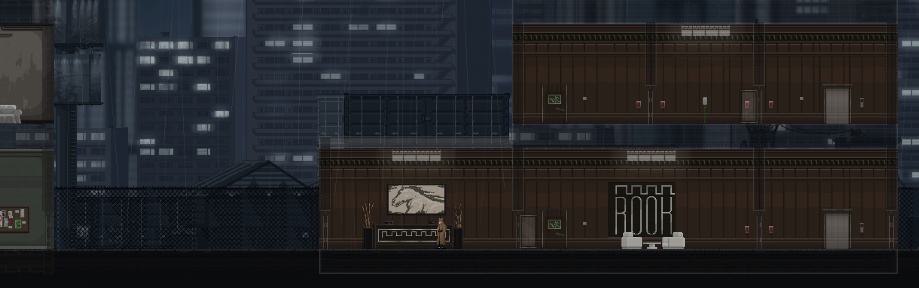

Gunpoint: The Setting

Wow. Response to my badly made video has been crazy, a whole order of magnitude more positive than I’d hoped. Actually slightly nervous now.

The best result of this is that a whole load of really talented people have offered their services, and many have already done great samples. There have also been a lot of very reasonable questions that made me realise my last post didn’t adequately define what I’m after. I called the current art a ‘rough guide’ without saying what about it should guide and what should be ignored.

So here’s a bit more about the idea for Gunpoint’s setting, look and mood.

World

Gunpoint is set in a big, largely empty city – or at least a largely empty part of a big city. It’s only about 20 years ahead of present day, so most technology is the same.

You

You’re a freelance spy. You get jobs from a site that lets agents choose from briefs written by anonymous clients. You wear a long coat and hat, and because you’re a spy, I would rather your face is either not clearly visible or has no recognisable features.

You’re the sort of person who acts very relaxed until he really needs to do something quickly, at which point you’re a flurry of motion and then back to trying to look nonchalant. I haven’t finalised your movement yet, but there’s a chance you may need to go from a casual shuffle/saunter/mosey into a semi-urgent run as you accelerate.

Gadgets

Through the agency, you buy a few rare high-tech gadgets to help with your work.

Hypertrousers: I always forget to tell people about the Hypertrousers. Compressed air actuators let you jump ridiculously far.

Gluon gloves: let you climb on any wall or ceiling. Adhesion does not actually use gluons. Gluon is a trademark of GluCorp and quantum physics is now a patent violation.

Crosslink: lets you connect any two electronic devices so that one triggers the other. Actually a cheap, widely available app for your phone, but so poorly marketed that only a handful of agents know it exists.

Tone

I want Gunpoint to have laughs, but it’s not set in a crazy world of whacky characters. People die suddenly and undeservedly, there are truly nasty people about, and justice is not always done. If you’ve seen Kiss Kiss Bang Bang, that’s the kind of tone: there are funny people in it, but they’re out of their depth in a dangerous underworld.

Look

Every mission takes place at night. It’ll also rain a lot. The main visual motif is meant to be the warm orange glow of a lit office block in the cold blue of a city at night. I have done a pretty lousy job of capturing that.

People

I’m fairly easy about style, but guards shouldn’t have too much individual personality, because there’ll often be a lot of them on screen at once.

The main restriction is that people have to be between 20 and 30 pixels tall. I said before that they could go over 24 if it’s part of a whole makeover for the scale of the game, but looking into it, even a makeover wouldn’t work with a 50 pixel tall character. Here’s the problem:

It’s nice and clear, but where the hell is my jump going to land me? The character needs to be small so the jumps can be big. And I want Gunpoint to work on a typical netbook res, 1024×600, all the way up to 1920×1200. The art challenge is to make a low-res character clear and appealing.

Thanks so much to everyone who’s put effort into the awesome samples I’ve seen so far. They’re giving me ideas already, so even the ones that don’t go in will have an effect.

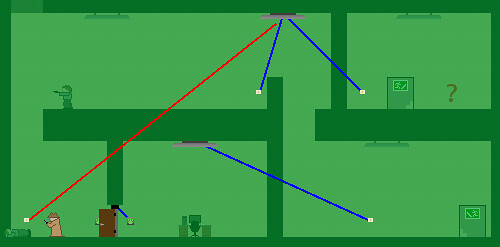

Gunpoint: The Mechanic

The game I’m making is about infiltration, but I’ve held off mentioning the way you do it until it’s actually in the game. It is now, and on Saturday night I sent it to around one hundred testers who kindly agreed to try it out. This was a little nerve wracking.

Before I go any further, if you signed up to test the latest version but haven’t played it yet, I’d really like you to play it before you read this. The reason I haven’t mentioned it before is that I wanted the first people to play it to do so fresh, to see if it makes sense without any external explanation.

It’s a tool called the Crosslink, which lets you rewire any device in the level to any other. So if there’s an electronically locked security door you want to open, you can use the Crosslink to wire a light switch to it, then press the switch to open the door.

But you don’t have to be the one who presses the switch: guards will use security hand scanners to open those doors, and hit light switches if they find themselves in the dark. So you can rewire those things to screw with them: a guard tries to turn the lights back on and finds it slams a door shut and traps him in the room. Trying to open it unlocks another door halfway across the level, letting the player into the building.

The idea is to give the player a lot of freedom to tinker with their environment and fuck with people. I wanted a system that gives you enough power that you can be creative, think of approaches that I hadn’t considered, and come up with your own way of playing. And I wanted a game where killing a guy is not the most interesting thing you can do to him.

Games that funnel you down a single path seem to be made from a perspective of, “What if the player is stupid? How can we make sure he can complete this?” I wanted to start from the question, “What if the player is smarter than me? How can I make something even he’ll enjoy?” I still want the barrier to entry to be low, but I don’t want it to double as a ceiling on the intricacy of what you can do.

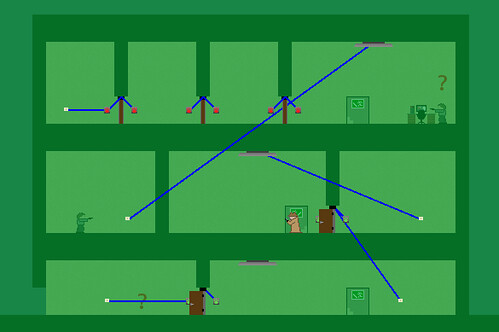

The results are making me very happy. I built a crude demo record/playback function into this prototype, so testers can send me a replay of their first attempt at the game, and I can watch how they dealt with each level. My plan was to see where the stumbling blocks were, what players tried to do but couldn’t, or didn’t try but could have. But it also shows the awesome solutions they came up with.

In the last one I watched, the player seems to rewire a building all wrong. I’m scratching my head when he hits a lightswitch, which isn’t connected to anything more interesting than a light. But a guard on that floor is by another switch, which he hits.

Instead of turning the light back on, it turns off the light on the top floor, causing the guard up there to open several security doors on the way to turn it back on. When he finally presses it, instead of the light coming back on, the door slams and locks behind him. The player just shuffles up the stairs and hacks the terminal he was trying to get to, while every guard on the level is trapped in a different darkened room.

That’s not the quickest or easiest way to do that level, nor one I’d ever tried, but it’s awesome to see people come up with their own plans. Early on, I’m happy for them to do that in a sort of sandbox context: it’s not necessary but it’s fun. Later on, I want to complicate the mechanic slightly so that this kind of ingenuity is actually necessary – putting devices on incompatible circuits so you have to trick the AI into bridging the gap for you.

Before I started thinking about this stuff, Irrational Games’ Steve Gaynor posted a great analysis of what leads to emergent game experiences. His conclusion is that meaningful state change is at the heart of it.

I totally agree, but I also wanted to come up with a more comprehensive list of the elements that make a game like Deus Ex so endlessly entertaining to me. Whether you want to call it emergence or something else, I decided on the components a game needs to have that kind of excitement:

1. State change. I must be able to change the state of important elements of the game between more interesting conditions than ‘alive’ and ‘dead’.

2. Connectedness. Elements should be able to affect each other, not just me.

3. True obstacles. The most direct and simple path cannot be viable, at least not for the ideal outcome.

4. Significance. Some elements must be obviously powerful, valuable, or consequential.

I’m satisfied I’ve covered 1 and 2 in Gunpoint now. 3 is sort of in there, in that you can’t open most stuff directly, but the simplest Crosslinks are usually viable solutions right now. That will change when I make incompatible circuits. 4 is less nailed down – it might come in the form of your objectives, VIPs and the like, it might be to do with the cops or rival agents showing up, or it might just be about guns and who has them.

The nice thing about the Crosslink mechanic is that it adds a lot of value to whatever else I put in, so it’s easier to justify spending some time on a new device. I’m always open to ideas for those – I’m planning some kind of metal detector or security camera, something triggered merely by presence, and an alarm that’ll summon guards to a particular floor when triggered. Any others?

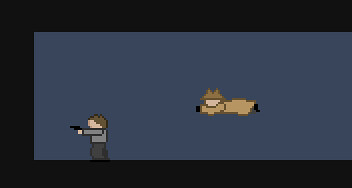

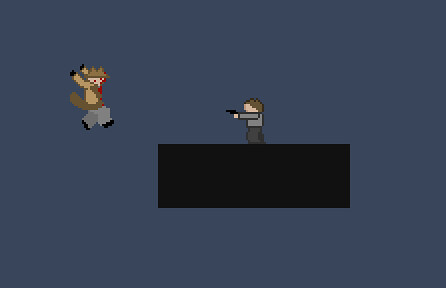

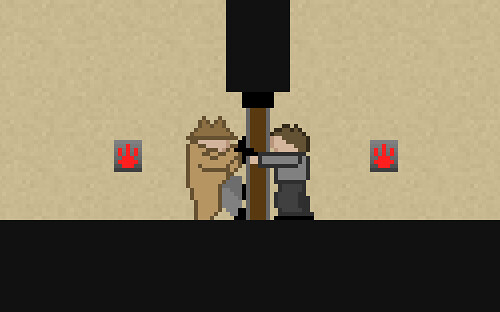

Gunpoint: Making The Jump

I had a chance to work on my game in my week off, the one I was going to call Private Dick. That name is increasingly pissing me off, so I’m calling it Gunpoint for now. How relevant that title becomes will depend a bit on how much fun it really is to be at gunpoint, or have other people there, and what kind of options I can reasonably code for those situations. Currently everyone with a gun shoots you in the face the instant they see you, and there’s a certain comforting reliability in that.

I’m almost at Milestone 2 – they’re really yard stones, these things, because I can’t have spent much more than ten hours on this thing since Milestone 1. Here’s the plan:

Milestone 1: movement fully working, however horrible it looks and shitty it feels.

Milestone 2: one hostile who shoots on sight, and can be pounced on and beaten unconscious.

Milestone 3: two devices that are interactible. I’ll talk about devices once I’ve got them working.

Milestone 4: one fully working level that’s fun.

Milestone 5: a dialogue system why not?

Milestone 6: narrative reduces grown men to hopeless fits of sobbing.

Milestone 7: the Citizen Kane of games.

So I’m not really thinking clearly more than two or three milestones ahead – my plans change too much with each one for that to be worthwhile, and anyway it’s kind of daunting.

About ten of the people who signed up to test my game played Milestone 1 and told me what they thought of it. This was awesome. Not least because most thought it was a lot less horrible-looking and shitty-feeling than I was expecting.

It’s also a really exciting and eye-opening thing to have people interact with something you created, and have reactions you didn’t expect. People overwhelmingly wanted a certain move added that I’d intentionally left out. And they were right: I’ve added it now and it profoundly improves the feel of the game.

That milestone was all about the jump: the tiny freelance agent you play can leap preposterous distances in any direction, and cling to anything he hits. This milestone, number 2, is about using that jump to pounce on angry gunmen while they’re not looking, then punching them in the face while you have them pinned to the ground.

That part took minutes, really, and is immediately and profoundly enjoyable. I hadn’t really thought about it before I coded it, but there’s no reason to force the player to let the gunman go after he’s hit him in the face once. I just made the mouse click smack him in the face, then return to the about-to-smack-him-in-the-face pose. You can jump off if you like, but in a survey of playtesters called me, 100% felt the need to beat him again and again and again, sometimes tapping out semi-musical rhythms with their facebeatings.

What was trickier was making the jump good enough that you could bet your life on it. One of the biggest complaints from the first test, even without any threats, was that people had trouble judging where their jump would go. I hadn’t even put a charge-meter in, and the strength of your jump increased quadratically as you held the button. A player’s instinctive grasp of basic movement mechanics doesn’t necessarily model quadratics effectively.

This was not a surprise. I knew what I wanted, ideally: a visual projection of the exact arc your jump will take. But like most of my plans, I had a few much easier back ups that wouldn’t work as well. Any kind of charge meter, I thought, would probably do.

The reason I’ve only spent ten hours working on this since the last milestone 5 weeks ago is not actually free time. It’s guts. Doing everything yourself is sometimes daunting.

The fun stuff: design, requires some less fun and harder stuff: coding. And the still quite fun stuff: coding, requires some much less fun, much harder and miserably unsatisfying stuff: art. When I’m not working on my game, it’s because I’m exhausted or distracted or just not in the mood to take on something that may, at any time, kick my ass.

What I’ve learnt from the whole process is this: guts. I’m not accustomed to putting time and effort into something and having it turn out shit, but I’ve found that when I actually get down and do it, it doesn’t take that much time and effort and not everyone thinks it’s shit. Just do it. Accept that not everything you do is going to be met with a steady stream of praise, venture outside your comfort zone and grow up.

That’s true enough for art, but it’s particularly true for coding. Predicting the arc of a player’s jump meant simulating the engine’s own internal vector analysis precisely, so that I could do all the calculations involved with it in a single frame. In other words, the game would have to play the jump out in its head thirty times a second, exactly the same way it would happen at normal speed. It seemed like it would involve an awful lot of trigonometry, which is tricky to code and tricky to compute. Having the game do it thirty times a second seemed like it would destroy performance.

Long story short, it was easy. If you’re smart about it, no sines, cosines or tangents are needed, just basic multiplications. It’s high school mathematics to model a rigid body under acceleration and derive a generalised formula for its position. And once you’ve got that, you just plug increasing values of time into it and create a dot at that position until you hit something. There are ways to make it more precise and reliable, but it already works so well that it’s completely changed the way I play.

I still don’t have a charge meter – I changed the system so that if you want to go further, you just click further away. It means you can make small, precise jumps without time pressure, and great long arcing ones without delay. And it feels great to leap six stories, through a window, and into the back of someone’s head. Then punch them to the beat of Seven Nation Army.

I whined a while ago about wanting to get to the point where the question is “Is this fun?” rather than “Why doesn’t this fucking, fucking work?” I’m there now, and from here until I’m done with the game or give up on it, there’ll always be “Is this fun?” questions to answer. There’ll still be many more things that don’t fucking, fucking work, but I’m tantalisingly close to having most of the building blocks to make real levels out of. Once I’m there, it gets really interesting.

Edit: just as I finish this, Sophie Houlden posts the text of her talk at World of Love, and it’s basically telling me to realise what I just realised.

Edit 2: Once I’ve tweaked it a bit, I could use some more testers to help me figure out if this iteration is fun yet. Any more volunteers? Mail me if so.

Edit 3: Now with animated gif.

Gunpoint: Coding

Programming is not what I’m naturally best at, and while it’s generally been easier than expected on Gunpoint, there is some friction. Some things are hard, and if you hit a hard thing after successfully coding lots of easy things, it seems maddeningly unfair.

You slip into a mindset where you expect things to work, which makes you angry rather than confused when they don’t. I’ve had to start spotting this mindset when it crops up, and taking a long, relaxing break before I go any further.

When I come back, I have to change gear. And the most useful way I’ve found to think of it is this:

It has completely lost it, and you have to be expect every sensible instruction to be met with screaming, preposterous bullshit.

Programmer: Hello Game, how are you feeling? I’d like to make this object stop when it hits a wall, if that’s OK with you.

Game: GRAVITY NO LONGER EXISTS!

Programmer: What?

Game: Every lightswitch in the world will fire a single red laser at one man’s head, and that man is… HIM!

Progammer: OK – I’m not sure how that’s related, but I’ll look into-

Game: I DON’T KNOW WHAT SPACE IS!

Programmer: The key, or…

Game: SPACE! SPACE! HORIZONTAL CO-ORDINATES! I have over five thousand references to ‘x’ and I’ve NEVER HEARD OF X.

Programmer: That’s… that’s how far right things are, Game. It’s the first thing we learned.

Game: NO! It’s a room! A room with a box, and a photocopier, and a lighting error, off the corner of Baker and 45th.

Programmer: …

Game: X IS A ROOM!

Programmer: Ohh, I actually did change the name of an old test level to that for a moment, I guess that’s what’s getting you confused – I’ll fix it.

Game: PRANKSPASM IS UNDEFINED!

Programmer: That one I’ll give you.

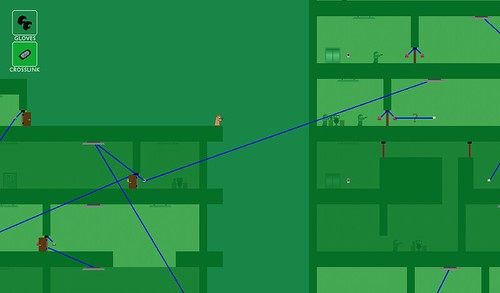

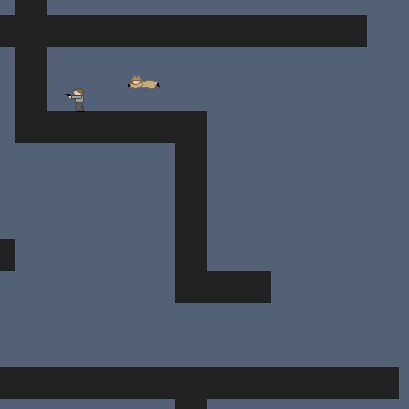

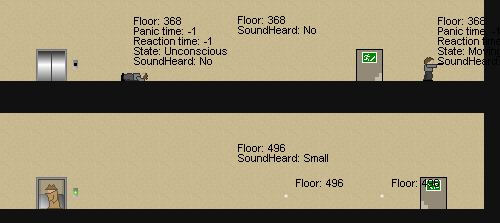

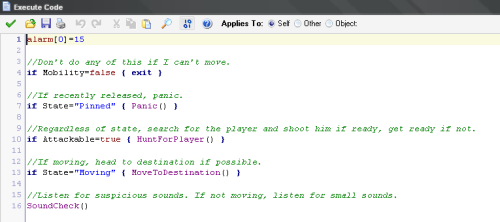

Gunpoint: AI

On some level, my game is going to be about fucking with people. When you get down to it, the reason I like Deus Ex isn’t because I have the choice of using a multitool or shooting a guy. It’s that I can trick the guy into doing what I want. If I don’t have the key to a door with a guard on the other side, I can just shoot a wall, and he’ll unlock it for me when he comes to investigate the noise.

People coming to investigate, in fact, seems to be the core rule in the most enjoyable deceptive play – whether it’s in Deus Ex, Thief or Hitman. So that was my one requirement for Gunpoint AI: you must be able to knowingly misdirect the AI. The fact that investigating suspicious noises is also semi convincing, semi effective behaviour for a guard is just a nice bonus.

I had a feeling this would be hard, and I knew it was probably a little too involved for a first project. But I was looking forward to trying, because AI is one of those nice juicy problems that’s too big to tackle. You have to break it down, and breaking things down in ways that make sense is one of my favourite things to do. I took philosophy and maths at university, so it’s about the only common thread in my voluntary education.

I wanted guards in office blocks to head to the source of suspicious noises, like gunshots or glass breaking, even if they weren’t on the same floor. It sounds dangerously like pathfinding, a famously sticky area, but I didn’t think it would come to anything like that. I can just break it down into a) how do I get to somewhere on my floor? and b) am I going to the sound itself or the stairs?

What I’m learning, increasingly, is that conceptual stuff is not the hard bit. Every high-level idea you have for how to translate a design concept into chunks of algorithmic code will probably work, and in fact is pretty easy to write. The hard part is a part I didn’t even realise was a part: order.

“I wanted guards in office blocks to head to the source of suspicious noises” – really? Did I want dead guards to respond to suspicious noises? Did I want guards to walk right past the player himself on his way back from breaking a window, in order to investigate the breaking of the window? Did I want guards who are being blown out of a window by the force of an explosion to stop, mid-air, and tell the others: “Oh hey, I’m closest to that broken window I was just flung through, I’ll go check out what caused it”? Did I want the guard who just shot you to run to your dead body and try to solve your murder?

Actually I kind of do, but that’s probably another game.

It’s easy to code what you want. But you don’t really know what you want until you’ve tried to explain it to a very, very stupid person. That was Socrates’ thing, in fact: he acted like an idiot to make people explain themselves to him on the most basic level, which usually revealed they didn’t truly understand their own beliefs. These days we have silicon hyperidiots to explain things to. They’re able to be much more stupid, many more times a second, than Socrates ever was. Coding is the Socratic method as an extreme sport.

Because the concept behind my AI system was simple, scripting it was getting increasingly complex. Every time I said something like, “Set this guard’s state to ‘alert’,” I had to first check that he wasn’t dead, or stuck, or in a lift, or being punched. And it wasn’t going to get any less fiddly: every time I added a new situation, I’d had to go back and add new exceptions to every line of code it could influence.

The only way I could make it simpler to code was to make it more complex to think about. It turns out that the nitty gritty of how an idea works in practice is a much more unwieldy beast than the high concept of what you want it to achieve, and it’s the former you really need to simplify.

So now I have an intricate system of connected timers, tracking five or so independent properties of the AI’s mental and physical state, and it’s a mess to think about. But in code, it’s remarkably straightforward. I’ve turned every sub-problem into a separate function with a human-readable name, replacing stuff like:

if ((sprite_index=sGunman && oPlayer.x > x) or (sprite_index=sGunmanLeft && x > oPlayer.x))

With: if HesInFrontOfUs

The top level code is now just this – the pink things are functions I’ve written that call in other chunks of code:

And after a lot of tinkering, and a few maddening variable-definition errors I never really got to the bottom of, it actually works. You can lure guards from their posts, hide the other side of the stairs and jump them when they come out. Or you can make a noise on one floor, then travel to another while the guard there runs to the one you just left. It’ll get more interesting once you have more of a toolset: right now all you can do in Gunpoint is jump on people and whale on them. But it’s already actual fun to screw with the AI, so I’m pretty excited about what I can do with it from here.

By the way, Spelunky creator Derek Yu put up a great guide about what stops people finishing games, and how to avoid it. Since he inspired me to start this, it’s nice of him to also inspire me to try and finish it.

Lastly, I need opinions: man-sized air vents are a cliche. But are they an annoying one, or just a tool that ultimately makes a game more fun? In some ways they’d fit with Gunpoint’s movement system, since they wouldn’t have to be floor-level for you to get to them. But I don’t know how sigh-worthy people find them these days.

Gunpoint’s Release Date’s Release Date’s Release Date

An Announcement

I will be announcing the release date of Gunpoint’s release date here tomorrow, Sunday the 26th of May.

To be clear, this is not an announcement of Gunpoint’s release date, nor is it an announcement of Gunpoint’s release date’s release date. It is an announcement of Gunpoint’s release date’s release date’s release date.

Update: We have been delighted with the community’s empassioned reaction to this announcement. These are just some of the high user-engagement social media interactions we have already logged:

“you’re a mean person”

@blaquened

“You’re a bad person”

@Nelsormensch

“This is bad and you should FEEL bad.”

@SJRB__

Gunpoint’s Release Date’s Release Date

An Announcement

I will be announcing Gunpoint’s release date here tomorrow, Monday the 27th of May.

To be clear, this is not an announcement of Gunpoint’s release date. As promised in our hit post Gunpoint’s Release Date’s Release Date’s Release Date, this is an announcement of Gunpoint’s release date’s release date.

Gunpoint’s release date remains unannounced, until tomorrow.